Lessons from Time: Is AI the New Dot Com Bubble?

- Matt McRae

- Jul 17, 2025

- 6 min read

In the late 1990s, the internet was new, exciting, and full of promise. Investors and entrepreneurs alike raced to stake their claims in the emerging digital frontier. All it took to raise capital was a clever name, a dot com domain, and a pitch deck. Revenue? Optional.

What followed is now infamous: between 1995 and 2000, the Nasdaq Composite (where tech stocks listed) surged over 570% as money flooded into tech stocks. But when the bubble burst in 2000, it wiped out trillions in value, took down thousands of companies, and ushered in a new age of financial caution - at least temporarily.

Nasdaq Composite Index (1995 to 2003)

Source: Koyfin (Nasdaq Composite - 01/01/1995 to 01/01/2003)

The tragedy of the dot com bubble wasn’t that the ideas were bad. Many of the businesses that failed were actually ahead of their time - web-based grocery delivery, social media, online communities, digital classifieds. The internet did eventually reshape every industry it touched. The issue wasn’t vision - it was monetisation.

At the heart of it was a simple problem: these companies couldn’t turn attention into revenue. Millions of users might have been clicking and browsing, but without a clear path to profit, "eyeballs on screens" proved to be a poor substitute for sustainable business models.

In this article, we explore the growing concerns that the ‘AI boom’ currently taking place may be destined for a similar fate - or whether investors will use the lessons of history to prevent another melt-up and collapse of equity markets.

Tales from the Nineties

For those who didn’t live through the 1990s, it’s hard to understand the euphoria that gripped the world with the advent of the internet. That’s why we’ve selected two examples of dot com-era companies to bring you up to speed.

Lesson #1 - Webvan

Webvan, launched in 1996, promised to revolutionise grocery shopping by offering home delivery ordered through a slick online platform. The company quickly raised hundreds of millions of dollars from investors (including Goldman Sachs and Sequoia Capital), went public in 1999, and at its peak had a market capitalisation of around US$8 billion.

So what went wrong?

At a time when few consumers had broadband and logistics infrastructure was immature, they attempted to vertically integrate everything - building warehouses, owning delivery fleets, and expanding into multiple cities simultaneously.

Webvan 'Checker' TV Commercial – Aired January 2001

From an economics standpoint, Webvan’s problem was unit economics: the cost to deliver each order far exceeded what they earned per customer. They hoped economies of scale would eventually make the model profitable - but by the time that could have happened, they had already burned through over US$1 billion in capital.

It’s a classic case of negative contribution margins: the more they grew, the more money they lost. Growth alone isn’t a solution when every additional sale digs the hole deeper.

By 2001, with the dot com bubble bursting and investors turning off the cash tap, Webvan couldn’t raise more capital. It filed for bankruptcy in July 2001 - just two years after its IPO.

What Can We Learn?

You can’t scale your way out of bad unit economics

Technology isn’t a moat if the business model doesn’t work

Being early is often the same as being wrong

Interestingly, Webvan’s core idea wasn’t wrong - Amazon and Woolworths are all modern versions of this concept. But they arrived at a time when technology, consumer behaviour, and delivery economics were better aligned.

Then there was Pets.com, launched in 1998, remembered for its sock puppet mascot and Super Bowl ad more than for its business (seriously check it out below). It sold pet supplies online and gained rapid brand recognition. But while customers loved the idea, shipping heavy bags of dog food at steep discounts proved financially ruinous.

Pets.com Superbowl XXXIV TV Ad - aired February 2000

The fundamental issue: Pets.com was selling low-margin goods (like dog food) at a loss, and shipping them long distances for free. Their most popular products were heavy, bulky, and low-value - the worst combination for a delivery business.

Put simply, their cost to serve was higher than the revenue per sale, and no amount of scale was going to reverse that. In February 2000, it raised US$82.5 million on the NASDAQ. Just 268 days later, it was bankrupt.

What Can We Learn?

Brand is not a business model. Pets.com had a household name but no path to profit

Gross margins matter. You can’t give things away and expect scale to save you

Unit economics must work before expansion

Ironically, what Pets.com envisioned is now thriving through modern companies like PetCircle here in Australia - who were able to figure out logistics, pricing, and customer retention in a very different environment.

The Survivors of Dot Com

While Webvan and Pets.com flamed out, not every dot com company met the same fate. Amazon, founded in 1994 as an online bookstore, is a standout example of how to grow a tech business with discipline.

Amazon did many of the same things its peers did - it raised capital, expanded aggressively, and embraced the web’s disruptive potential. But it also did something critical that others didn’t: it focused relentlessly on customer value, efficient logistics, and a clear path to monetisation.

Even in the early days, Amazon generated revenue with every sale. It didn’t give away products to grow. And rather than build out capital-intensive infrastructure all at once, it expanded step by step, constantly reinvesting in better systems, better fulfilment, and better service.

In 2000, while others were going public with no revenue or profits, Amazon was already handling millions of orders, building its brand through reliable service and convenience - not just advertising. Though it faced its own share of criticism and volatility during the crash, Amazon survived and thrived because the underlying economics of the business made sense.

While the dot com era delivered both flameouts and winners, the key differentiator was economic discipline. That’s a lesson worth revisiting today as we navigate the excitement - and risks - of the AI age.

Echoes of the Past - The AI Gold Rush

Fast-forward to today, and we’re witnessing a new technological boom. This time, the driver is artificial intelligence - and in particular, the rise of large language models (LLMs) like OpenAI’s GPT, Google’s Gemini, and Anthropic’s Claude.

Much like during the dot com era, investors are pouring billions into the AI space. Startups are racing to launch chatbots, productivity tools, code assistants, and AI agents built on top of foundational models. Some are genuinely impressive. Many are not. And a growing number face the same economic challenges that plagued their dot com predecessors: no clear path to monetisation.

We’re seeing:

Free tools with no pricing model

Apps with marginal differentiation from competitors

High user acquisition costs in a crowded market

A dependency on someone else’s (often expensive) foundational model

As before, the attention is real - but attention is not the same as value.

Where Might Value Emerge?

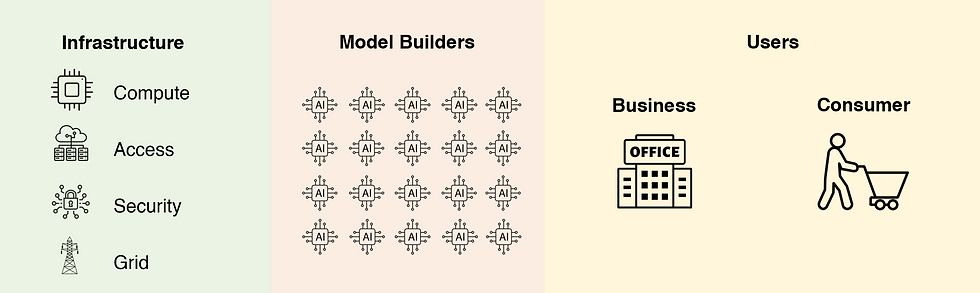

Rather than betting on the winners among AI applications, many investors are looking instead at the enablers - the companies selling the pickaxes in this gold rush.

These include:

Compute: Designing and building the chips that power most of the world’s AI workloads

Access: The massive physical infrastructure required to train and deploy models

Security: The companies building software to protect business operations from bad guys with AI.

Grid: As AI demand grows, so does the need for energy and specialised cooling infrastructure.

The AI Supply Chain

This “picks and shovels” strategy doesn’t require you to predict which app or model will dominate - only that AI is real, and someone will need to power it.

Lessons Remembered, Not Yet Repeated

We don’t know yet whether the AI boom will end in a similar bust to the dot com era. It’s entirely possible that we’re entering a new phase of euphoric investment, rapid adoption, and surging valuations - followed, perhaps, by painful resets and failures.

But it’s also possible that this time, more investors and operators will remember the lessons of the past.

History reminds us that technology alone is not a business model, and that attention without monetisation is just noise. During the dot com bubble, thousands of genuinely useful products were created - but many couldn’t survive because they never figured out how to turn users into revenue.

Today, as the AI ecosystem rapidly expands, the same risk looms. The difference is that we now have the benefit of hindsight.

At Bratton Wealth, our view is that we don’t need to predict the exact winners of the AI age. We can take a more disciplined approach - favouring sound business models, defensible margins, and infrastructure plays that benefit from rising demand without needing to bet on specific outcomes.

We can’t eliminate risk entirely - but we can approach this new wave with discipline, patience, and a clear memory of what happens when excitement overtakes economics.

Comments